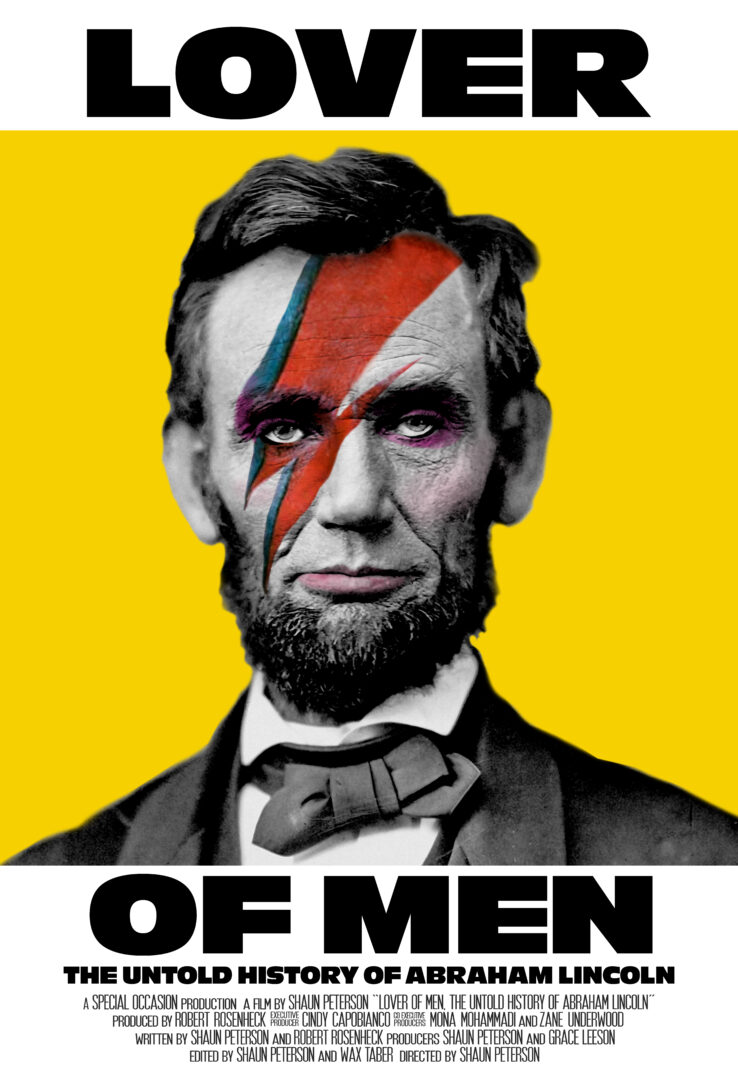

5Q: Lover of Men: The Untold History of Abraham Lincoln

Historians have argued for decades over whether Abraham Lincoln had romantic or sexual relationships with men. A new documentary, “Lover of Men: The Untold History of Abraham Lincoln,” brings nearly 20 historians and scholars across disciplines together to formulate the conclusion that he did. Using never-before-seen photographs and letters, interviews, and reenactments, the film details Lincoln’s romantic relationships with four men then widens its lens into the history of human sexual fluidity and focuses on the differences between the 19th century and today.

Presidential and political historian Thomas Balcerski, a professor at Occidental College and Eastern Connecticut State University, picks up where previous historians left off to bring fresh eyes to old documents.

Lavender: What initially drew you to study this topic and aspect of Lincoln?

Balcerski: Sometimes you pick up a book, look at it, and say, “This looks interesting!” and that was the case when I picked up Jonathan Ned Katz’s “Love Stories.” He is an eminent senior historian of queer history, really a pioneer, and, to use another metaphor, a godfather of LGBTQ history.

He gives a wonderful performance in the film as he reads correspondence from Joshua Speed and Abraham Lincoln that references “lavender spots, soft as May violets.” In his book, “Love Stories,” the first chapter is dedicated to the romance, I’ll call it, between Lincoln and Speed. Jonathan was already aware of this, it turns out, for decades. As I was drawn in, I became more interested, as well, in what historians have known. It became my quest to figure out who knew first and who decided not to tell. Because now we know and now we’re telling with this film.

There was also an eminent sex researcher, I’ll call him, but really a clinical psychologist who worked for the great sex researcher Alfred Kinsey, named Clarence Tripp. His book on the intimate world of Abraham Lincoln took an even broader purview of Lincoln’s life [and] went beyond the relationship with Joshua Speed.

And now I am hoping, in my own research and my own book project, to expand and elaborate upon this scholarship. I’m so glad the film is making a really strong, powerful visual argument for these relationships and for Lincoln as a lover of men.

There are a lot of people, including scholars, who want to not believe or dismiss this discourse around Lincoln’s relationships. Why do you think that is and what do you say to them?

One reason I’m doing this film is I want to take this mass medium and make a case for the public, but also for my fellow historians. I’ll say this: historians won’t listen to me making this argument academically. They didn’t listen to Jonathan Ned Katz, they didn’t listen to Tripp. [They are] kind of put over here to the side, queer historians working outside of academic affiliations. I come along and say, “All right, I have a Ph.D. from an Ivy League school. I work at a university in New England. What about me? Are you going to just say I don’t count either?”

It’s a bit of a credentialing battle. You have to be serious enough, you have to be accepted enough within this very tight-knit community of Lincoln scholars. The epicenter is Springfield, Ill., where the power is held, where literally the documents reside and the film brings them to light for the first time.

But I also think I’m using the same tools as these same historians and I just immediately disagree with their interpretations. I mean, it’s really about a disagreement and an argument, in the best sense, that you take a position, you present evidence, and you hopefully have a discussion to follow. The problem has been the shutting down, really the dismissal of this entire argument about Lincoln’s sexuality that has been done in so many ways.

It’s a little bit about how the profession works, it’s a little bit about how queer readings are so easily shunted because of decades of homophobia that have been layered on all aspects of American life.

Has there been new scholarship or breakthroughs? What has led to the growth of interest around this topic and the creation of this documentary?

You literally need to refresh the roots of historical scholarship; you need new people. It takes us four years of undergrad, seven to 10 years for a Ph.D. We write our first books usually based on a dissertation, and no one is going to write a queer Lincoln dissertation because of the risks involved. You have to get tenure; you need job security.

It’s been 20 years in the making for me, it’s been 60 years in the making for Jonathan Ned Katz. It just takes so long. It takes decades for historical knowledge to disseminate. This is glacial stuff. Certain discoveries get glamorized — very occasionally they will rise to the level where it becomes a public value. I see this most frequently in archaeological discovery and other kinds of physical remains. When it comes to document discovery, it’s a lot rarer.

Libraries and archives are very good at what they do. All of this is there, and it’s been there for centuries. Even the Lincoln letters have been known since the 1870s. Fortunately, search tools have changed the way we can access information. There’s been newly accessible sources. Not newly discovered, but newly accessible. As a 21st-century researcher, the accessibility of sources is far greater than what Jonathan Ned Katz had. So, I am “finding” new things. They’ve been there, but I’m finding them. Therefore, scholarship is finding them. But again, it’s just painfully slow, both in terms of the dissemination of that knowledge and the acceptance of the argument.

Can you explain what types of coded language were used that make deciphering historical letters challenging?

Were you aware before watching the film and before learning about the Lincoln-Speed relationship, that, at least by the 20th century and probably the 19th, the very word “lavender” was a coded word for queer sexuality or attraction, for homosexuality, as it would have been called at that period.

You have to go beyond Lincoln; you have to have an understanding of history and language. The problem is when you take a word you think you know and you apply it the way we mean it today.

“Lavender” is a good example. “Intimacy” is another word. Speed will say, “No two men were ever more intimate.” Then, Robert Todd Lincoln will say of his father, “Joshua Speed was my father’s most intimate friend.” So, you have Speed himself and Robert Lincoln, the son, using the exact same word. That’s not a coincidence, that’s a pattern. But to know what it means and to know how intimacy was coded with sexual language is to, again, explore a broader history from this period.

So, every time you pick up a source, you have to find those phrases, those words, those metaphors that have meaning and decode or unpack them.

What do you want viewers to walk away from this film knowing or thinking about?

I want them to leave uplifted. We are out and proud: the cast, the crew, the film. There is no hiding that. We want all people to watch this; we especially want queer people to watch this. I want my community that I feel a part of to watch this film and to be uplifted and then to turn to the person next to you and say, “Well, what do you think?” I want conversation. I want discussion.

What the film does is it opens up questions about our past. If you embrace this idea that queer people have a past, that it isn’t just some new thing, but a centuries-long, documented, recorded history that changes with time — which should be basic stuff, you would hope. But I teach American history, I teach queer history. Nothing should be taken for granted, ever. So, it has to be stated.

I want viewers who are more skeptical, who come in with loaded questions about this film, about the whole nature of a project about human sexuality, about Abraham Lincoln … I want them to see the film, too. I don’t expect them to be as happy and that would be a good thing. We want people to be critical of us.

It just has to be said: this is a special film. This doesn’t come along but once a generation. Frankly, there aren’t very many films like this.

Note: This interview was edited for length.

To check out the film trailer, click HERE

Lover of Men: The Untold History of Abraham Lincoln opens in theaters September 6 and has partnered with the Human Rights Campaign. Tickets purchased to see the film in theaters opening weekend via this custom Fandango link will directly benefit HRC. For more information, head to www.loverofmen.com.

5200 Willson Road, Suite 316 • Edina, MN 55424

©2025 Lavender Media, Inc.

PICKUP AT ONE OF OUR DISTRIBUTION SITES IS LIMITED TO ONE COPY PER PERSON